From Survival to Transformation

Part I - Learning I Might Have Cancer

March split my life open like a fault line.

For months, I had been begging for help. My body was screaming—abdomen distended like I was carrying something monstrous, pain that felt like glass shards moving through my organs, vomiting blood that left metallic traces on my tongue for hours. I called my primary care doctor's office so many times I memorized the hold music. Appointments kept getting switched to rushed FaceTime calls where doctors squinted at me through pixelated screens, then cancelled altogether with robotic voicemails citing "scheduling conflicts."

The knot in my abdomen had been growing since February as far as i could feel, hard and alien under my skin. I could feel it when I lay down, when I sat up, when I breathed too deeply. It was the size of a plum. I kept asking people to feel it—friends, anyone who would listen—desperate for validation that this wasn't normal, that something was terribly wrong.

Right before I went to the ER, exhaustion won. I left a message in my patient portal, fingers shaking with rage: "I guess I'll just go to the fucking ER, since I can't get an appointment and keep getting cancelled on.”

The ER was fluorescent-bright and smelled like disinfectant trying to mask something rotten. I sat in that waiting room for three hours, doubled over in a plastic chair after vomiting in the waiting room bathroom, watching people with visible injuries get called back while I remained invisible. When they finally called my name, the triage nurse barely looked up from his computer as I described months of symptoms. He didn't ask me to rate my pain. When I stood up from the wheelchair and asked her to feel the mass protruding from my abdomen, he just said “yeah, I can feel that.” Meanwhile the guy after me, able to walk, not seemingly in discomfort, was asked his pain level and offered morphine injection while I was offered two Tylenol - a triggereing a flashback to that same room in 2017 when they didn’t believe y pain until my CT scan came back and I was rushed into emergency surgery because my intestines were pushing out through my navel.

It wasn't until the CT scan that their entire demeanor changed.

The doctor walked into my room with that particular kind of gravity that immediately tells you your life is about to be divided into before and after. The first thing he asked me was: "Do you want to have children someday?"

I stared at him, confused. What kind of fucking question is that? Of course I wanted children. I told him yes, my voice smaller than I intended. He paused, and in that pause, I could feel my future reshaping itself.

"Well, it looks like you have an abnormally massive growth in your uterus that has irregularly grown since your myomectomy in 2017. And in addition, it appears that you have cancer and that it has metastasized. Your scan shows tumors near your kidney, in your abdomen, and near your left lung. I am so sorry."

The words hit me like a physical blow. Cancer. Metastasized. I didn't say anything because there was nothing to say. My mind went completely blank, like someone had unplugged me from myself. I just remember the mechanical motion of dialing Autumn's number, then Shastine's when she didn't answer. My fingers moved without conscious thought while somewhere in the background I heard the words "You need to be admitted."

That night, alone in a hospital bed with an IV dripping into my arm and machines beeping around me like electronic prayers, I understood that everything I thought I knew about my life had just become irrelevant. The woman who woke up that morning was gone. In her place was someone who had to learn an entirely new language—oncology, staging, prognosis, survival rates.

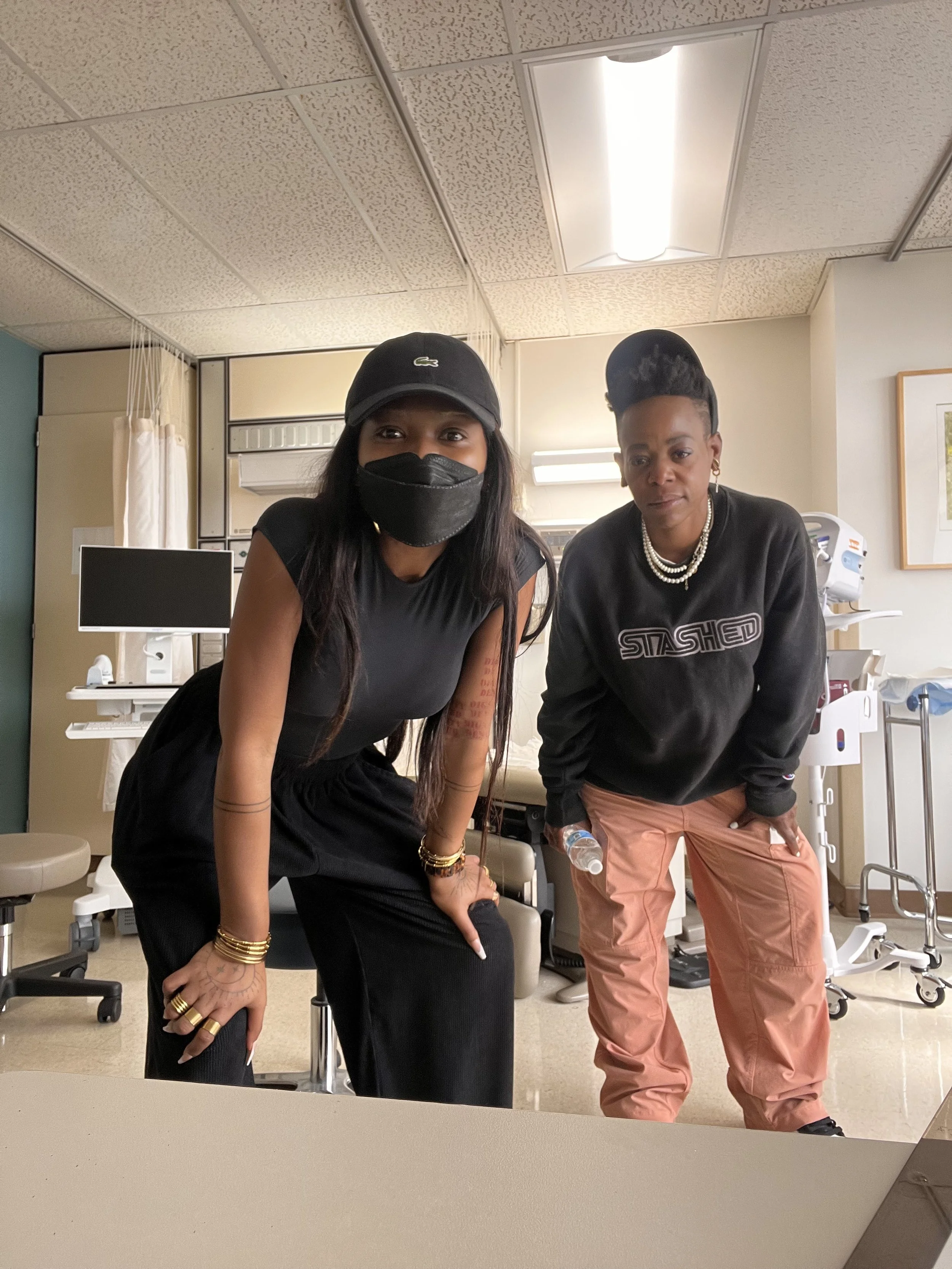

When I had called Autumn from that ER room, it felt like the most natural thing in the world. Autumn is my sister from another mother, my kindred spirit, a fellow Black woman who sees and understands me in ways that feel rare and sacred. Our collaboration on “Resting Our Eyes”—the inaugural exhibition we co-curated in San Francisco that centered Black women’s liberation through leisure and adornment—had shown me the depth of our creative and spiritual alignment. We had brought together works by Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson, Mickalene Thomas, and 17 other multi-generational Black artists, creating a space that affirmed Black women’s right to rest, beauty, and joy as radical acts of resistance.

Although she hadn’t been able to answer while I was in the ER, Autumn called back the next morning and immediately flew up to Oakland from LA. She spent that night in the hospital with me and immediately began advocating for me, showing up without me even asking in perfect alignment and understanding of the type of care Black women can receive in hospitals and the ways we are often mistreated, our pain dismissed. She knew, without me having to explain, that I needed someone who could speak the language of medical advocacy, someone who wouldn’t let them minimize my experience or rush through explanations.

Somehow, her arrival instantly calmed me and my ability to re-center myself was restored. There’s something powerful about having another Black woman witness your vulnerability and pain, someone who doesn’t need you to perform strength or make them comfortable with your fear. Autumn’s presence reminded me that I wasn’t navigating this alone, that the same collaborative spirit we’d brought to “Resting Our Eyes”—that deep understanding of how Black women care for each other—was now being directed toward my literal survival.

Part II: Lessons in Survival & The BML Diagnosis in June

Last fall, during my residency at Pilchuck Glass School, I created “Edge of Survival”—an installation that became my manifesto written in red neon light. Even before my diagnosis, my work was informed by survival—the daily navigation required as a dark-skinned Black gay woman, the constant code-switching and hypervigilance that comes with existing in spaces not designed for you. My Black feminist praxis had always been about more than theory; it was about literal survival, about the ways we create light and community in hostile environments.

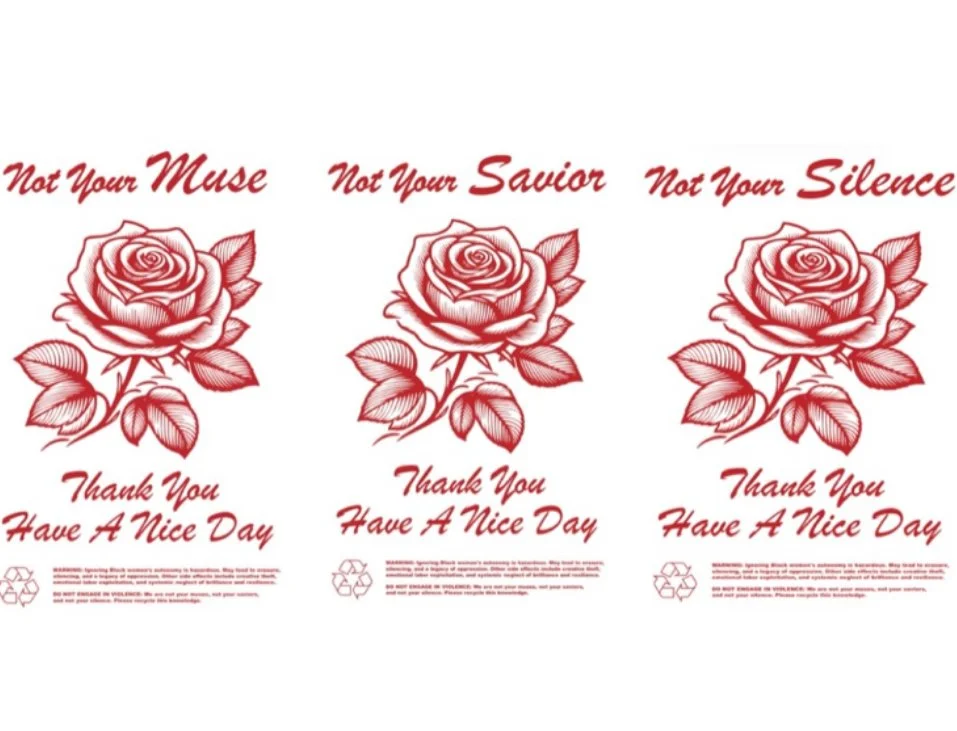

The phrases “Not Your Muse,” “Not Your Savior,” and “Not Your Silence” pulsed with the rhythm of a heartbeat, each word hand-bent from glass tubing that I shaped while thinking about Audre Lorde’s essays on survival and self-definition. Working with neon at Pilchuck was revelatory. There’s something about bending glass at 2100 degrees that mirrors the process of transformation—taking something solid and making it malleable through heat and pressure, shaping it into something that could hold light.

The installation drew on Lorde’s insistence that Black women define themselves on their own terms, that we resist the world’s efforts to consume us in passive or decorative roles. “Not Your Muse” rejected the objectification that reduces Black women to fantasy. “Not Your Savior” addressed the burden we often bear in supporting and saving others, while “Not Your Silence” defied the suppression of Black voices. The work pulsed like a living thing, like the heartbeat of resistance itself.

I had no idea then that within months, survival would take on an entirely different meaning.

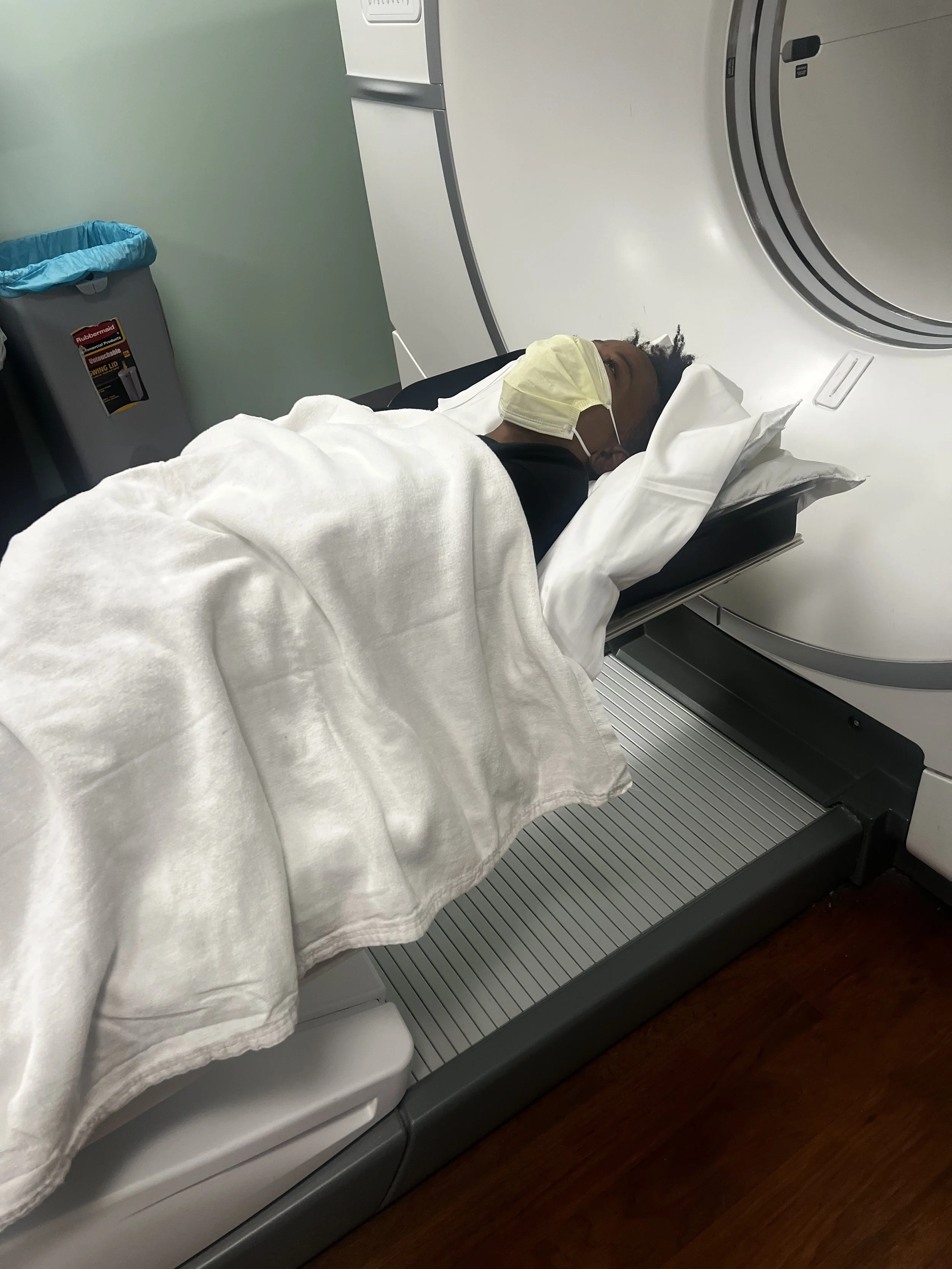

What followed my March ER visit were months that felt like living in medical purgatory. Blood draws that left my arms bruised and track-marked, CT scans where the contrast dye made me feel like my veins were filled with liquid metal, and waiting rooms that became second homes. I memorized the motivational posters on hospital walls,I could navigate the maze of Alta Bates by smell alone.

The potential cancer diagnosis hung over everything like a storm cloud for three months until June, when it transformed into something else entirely: BML—Benign Metastasizing Leiomyomatosis. By my side was Autumn, who had flown up from LA to advocate and be a witness when the gynecological oncologist broke the news of this diagnosis. A rare condition where benign uterine fibroids metastasize like cancer but aren’t actually malignant, it’s so rare that when Autumn asked about research studies I could be a part of, the doctor’s response was blunt: “Like, nobody has this.”

She wasn’t exaggerating. Less than 200 documented cases exist, with even less research and medical writings about it. I became a medical unicorn, a case study, a mystery that required consultations with specialists from UCLA, Stanford, Sutter Health, UC Davis, and UCSF—all of whom, she said, would be meeting and reviewing all my scans together.

Even then, there were still questions about the tumors in my abdomen that were appearing to not be benign but some kind of sarcomas. It took two failed PET scans later (I can write an entire post about all the failing.) and just a week before arriving at Alfred that a final PET scan revealed those too are also benign. But—they are all still growing, still causing pain, still metastasizing.

The relief of “benign” was immediately complicated by the reality of “metastasizing.” These weren’t cancer cells, but they were still growing around my lungs, my abdomen, my pelvis. They still required treatment, monitoring, surgical interventions. The word “benign” felt like a cruel joke—there was nothing benign about the way this condition was reshaping my life, my body, my future. And most of all, I still have one pushing on my lower spine making a full night’s sleep impossible.

The physical toll has been relentless and exhausting in ways I never imagined. Tumors pressing against my intestines make it hard to breathe deeply, to eat. The one near my kidney sends shooting pains down my back when I move wrong. I’ve learned to navigate a new landscape of fatigue that isn’t fixed by sleep, pain that comes in waves, and the constant mental load of managing a complex medical condition.

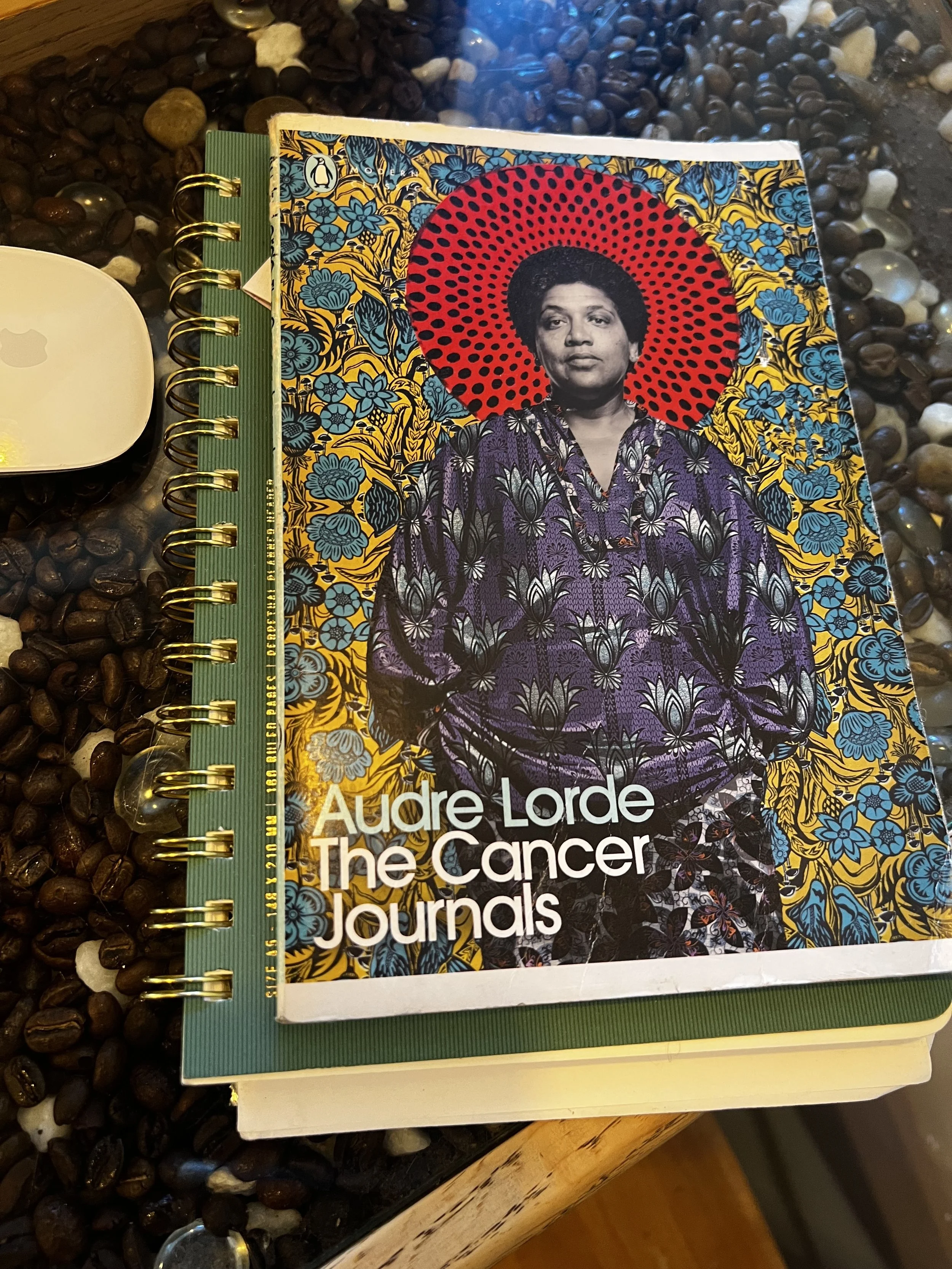

But somewhere in the midst of all this medical chaos, I found myself returning obsessively to Audre Lorde’s words: “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation.” I read “The Cancer Journals” while sitting in infusion centers, her words echoing through the beeping of IV machines. She wrote about survival not as passive endurance but as active resistance, and suddenly I understood that my art practice wasn’t separate from my medical journey—it was the same fight I’d been fighting all along, just with different stakes.

This year has taught me that survival isn’t just about staying alive. It’s about refusing to be diminished by the forces that seek to consume you, whether they’re medical, social, or systemic. It’s about the radical act of continuing to create, to dream, to insist on your own voice even when your body is betraying you and the medical system is failing you.

I’ve lost people along the way - mainly to the inevitable shifting that happens when your life takes an unexpected turn and not everyone can follow. Each loss has been a teacher, showing me something about what it means to hold space for grief while still moving forward, to honor what was while building what’s next. Their voices have become part of the work, part of the neon that will pulse with life in the studios I’m about to enter. Im a big fan from past experiences of now letting shit go. When something or someone, a relationship doesnt work- fuck it. Let shit go. Fail fast because the reality is this:

I currently have nine tumors —some visible on scans, others that can be felt during examinations. Nine. Each one requires monitoring, measuring, and documentation. Living with BML means my body has become a constellation of nine growths that need constant surveillance. Every few months, I have to fly back home to California for testing—CT scans, MRIs, blood work, appointments with specialists who are still learning about this rare condition alongside me while making sure the tumors don’t become malignant.

The logistics alone are exhausting: coordinating with insurance, finding flights for myself and Nino that work around MFA deadlines, arranging care for Nino during radioactive imaging, packing medical records and imaging files like other people pack vacation clothes. But it's the emotional toll that's hardest—the way each trip home reminds me that my body houses nine unwelcome tenants, that survival requires this constant negotiation between living my life and monitoring for changes that could shift everything again.

Part III: The Transformation: From Oakland to Alfred

Choosing to pursue my MFA at Alfred University while navigating BML felt like jumping off a cliff and hoping I’d learn to fly on the way down. There were moments—plenty of them—when the practical voice in my head questioned whether I could handle the rigor of graduate school while managing doctor appointments, insurance battles, and the unpredictability of a rare medical condition.

But then I remembered that for me, art has never been a luxury or hobby—it’s survival technology. It’s how I make sense of trauma, how I transform pain into something that can serve others, how I insist on my own voice when the world tries to silence me.

Alfred University’s Sculpture Dimensional Studies program isn’t just prestigious—it’s legendary in the glass world. The hot shop, the neon facilities, the access to equipment and mentorship that most artists only dream of. When I got accepted, it felt like the universe was saying yes to my survival, yes to my transformation, yes to the work that’s been burning inside me.

The transition from Oakland to Alfred, New York has been profound in ways I’m still processing. Oakland held my diagnosis, my fear, my early fumbling toward understanding what survival could look like. Oakland also held trauma - pain from people, strangers attacking me, my car being stolen, my apartment being broken into (twice). Alfred represents something else entirely—the space to push that understanding further, to explore how neon can serve as both medium and metaphor for the ways Black women create light in spaces designed to diminish us.

During orientation, I took a video on the tour that showed me exactly why this place is ranked number one in glass science and engineering. I had already known Alfred University is the only university in the nation that offers M.S. and Ph.D. programs in Glass Science, but what blew my mind wasn’t just the prestige—it was seeing how they’re advancing traditional technologies like fire, glass, and raw materials into revolutionary applications.

I learned about glass they’ve developed for open heart surgery closures that achieve a 94% non-infection rate—the kind of breakthrough that saves lives because infection is what people usually die from in that kind of surgery. Standing in those labs, listening to the engineering Dr., seeing one of a kind machines, I understood that I’m not just here to make art—I’m here to be part of a tradition that transforms raw elements into technologies that literally keep people alive.

The 3D printing capabilities here are beyond anything I’ve ever seen. They have machines that can print with materials being developed for space exploration—components that are actually going on shuttles to Mars and the Moon. Doing all of this and also welcoming us graduate students to be a part of this work was grounding. Walking through those facilities, I realized I’m entering a place where the boundary between art and life-saving technology doesn’t exist.

Given my background being in science—being pushed into that field by my parents with no ill will to them—made it all the more bittersweet that I am where I’m supposed to be. Even though I was damn good in biology and science, my heart was always in art. Standing in those labs, seeing how my scientific knowledge could actually enhance my artistic practice rather than compete with it, felt like coming full circle. Who I am as a person, with my willingness to survive and transform, suddenly made complete sense in this context. It’s validating to know that I made the right move and affirms trusting myself in knowing what I need. This is when I felt certain I am supposed to be here and anxiety and overwhelming feelings upon arriving started to diminish.

But what really got me during the tour was when the foundations department emphasized their commitment to interdisciplinary studies. It felt so much like how I naturally build community—breaking down silos, creating connections across different ways of knowing, insisting that the boundaries between disciplines are artificial and limiting. The engineering program is incredibly welcoming to collaboration with the art department, actively encouraging art graduate students to bring our ideas and perspectives into their labs and research projects. They don’t just tolerate interdisciplinary work—they celebrate it.

It’s like community but make it grad school, you know? The same energy I’ve always brought to organizing, to building bridges between different communities and practices, is not just welcome here—it’s essential to how this place operates. I realized that my approach to survival, which has always been about weaving together different forms of knowledge and support, is exactly what makes this environment so powerful.

I’m creating a home base that can hold both the solitude necessary for deep work and the community I’ll build with my cohort. The landscape here is so different from California—rolling hills, dramatic skies, the kind of quiet that makes you hear your own thoughts more clearly. There’s something about this place, dedicated entirely to the act of making at the highest level of technical innovation, that feels like the perfect container for this next chapter.

From Survival to Community

I’m writing this from Alfred, surrounded by boxes that still need unpacking and sketches for projects that exist only in my imagination for now. Outside my window, the landscape is preparing for winter, and I’m preparing for the most intensive creative period of my life.

This blog will document the journey—the 3 AM studio revelations, the technical failures that teach me more than successes, the conversations with faculty and cohort that crack open new possibilities. But more than that, it will be a record of transformation. Of what it means to choose growth in the face of uncertainty, to insist on your own voice even when—especially when—the world tries to silence you.

This isn’t just my survival story. It’s a shared journey, one that acknowledges the ancestors who paved the way, the community that holds me up when I can’t hold myself, and the future Black women artists who will see something of themselves reflected in this light I’m creating.

I think about Audre Lorde, who wrote some of her most powerful work while battling cancer, who transformed her diagnosis into a catalyst for deeper truth-telling. I think about all the Black women who have had to become their own saviors, who have refused silence, who have insisted on their right to exist and create and thrive.

Thank you for being here at the beginning. This is only the start, and I have a feeling it’s going to be extraordinary.

Follow along at tahirahrasheed.com as I document this journey from survival to transformation. If you’d like to support my work and education, you can find links organized by my friends to my GoFundMe and registry below. Your support helps make this metamorphosis possible.